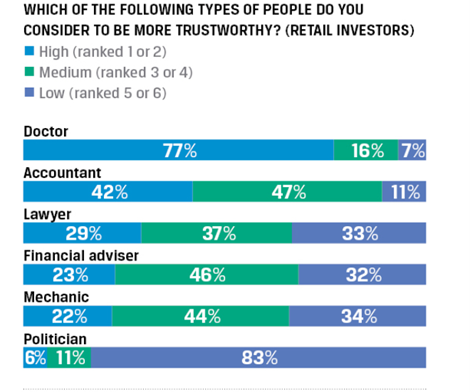

When it comes to trustworthy professions, what professions would you typically think of? Take a second to think about some professions. Ok. What professions did you come up with? What might be top of mind for you could be “doctor”, “accountant”, or maybe “firefighter”. Much to my chagrin, I doubt that “financial advisor” came up for you during this thought exercise. Don’t feel bad, I’m used to it. You also aren’t alone in thinking that way. Many people thought financial advisors were just as trustworthy as mechanics (no offense to the mechanics out there).

Why is the typical financial advisor considered untrustworthy? Pretend your investment portfolio is your car and the financial advisor is a mechanic. If you go to take your car [investment portfolio] to the shop [the financial advisor’s office], it’s because you feel something is wrong with your investment portfolio. You expect the person diagnosing the problem to have your best interest in mind when consulting you on what’s going on. Unfortunately, many times that person doesn’t have your best interest in mind. The first step in making sure that you are getting sound advice is to find an advisor who is a fiduciary. A fiduciary is an advisor who is, by law, required to have the best interest of their client in mind before their interest at all times.

Now assume that you are still working with an advisor who is not a fiduciary. They might tell you that your portfolio is out of whack and that you need a tune-up. The next step you should take is to get a second opinion, especially if they recommend drastic changes to your investment strategy. After that, you should weigh the economic costs of making the change vs not making the change. Using the car and mechanic comparison for your investment portfolio and your financial advisor, would the changes make the engine of the car purr, would the changes make the engine sputter, or would the engine already run perfectly fine without any changes?

In this article, we’ll take a look at some products that you should at a bare minimum be skeptical of or probably should avoid altogether. Remember that no widely available financial product is bad in a vacuum, but the financial product has to be appropriate for the investor buying the product. By the end of the article, you’ll be well-equipped with the necessary tools to spot what to look for and also what to steer clear of.

Annuities

Annuities tend to get a bad reputation because they are complex and misunderstood by the general public. We regularly meet with clients that either have a bad annuity, are not sure of this annuity they bought, or are being sold an annuity by someone and want to get a second opinion from us before they potentially buy. Again, annuities as a product when discussed in a vacuum are not inherently bad. However, how annuities are misused, marketed, and sold is often unfortunately bad. Many broker-dealers that focus on annuity sales (or market annuities to their advisors as a complement to a successful financial plan) also have sales incentives to their advisors so that the advisors are more incentivized to sell as many annuities as possible. With that type of mindset, some advisors of that kind of broker-dealer may start thinking that annuities are good for any client regardless of that client’s unique situation.

Example:

Mr. and Mrs. Adams have $100,000 in their bank account and $100,000 in a brokerage account invested in stocks and bonds. They are 70 years old and have no other assets. Mr. Adams’ health is declining, and they think they will need to use some of the money in the next 1-2 years to help pay for his medical bills. They don’t want to take any stock market risk for the next 5 years because they are nervous after recently binge-watching cable news segments about how the economy will collapse any day now. They meet with their advisor, Mr. Wormwood, to help them figure out what to do with their brokerage account.

Mr. Wormwood meets with them and recommends that they move the $100,000 in the brokerage account into an annuity. Mr. Wormwood says that the annuity can’t lose money and is guaranteed to earn between 0-5% per year based on market performance. He says, “If you are wrong and the market does well, you can earn up to 5% on your money. If you are right and the economy does crash, you don’t lose anything. Also, whenever you want to exchange the annuity’s value for a guaranteed lifetime income of $7,000 per year, you can do so at any time.” Mr. and Mrs. Adams like what they hear and sign the paperwork to move the $100,000 to this new annuity.

A year goes by, and unfortunately, Mr. Adams’ health is declining. They need $25,000 from the new annuity, so they call Mr. Wormwood to request the funds. Mrs. Adams meets with him and they have the following conversation:

Mr. Wormwood: “I’m sorry to hear that, but you’ll need to take out $26,251.35 to net $25,000 from the annuity. You need to factor in the surrender charge.”

Mrs. Adams: “What is this surrender charge? You said we won’t lose any money if the market goes down. The market did nothing since we bought this annuity, so the $100,000 that we put into the annuity is still worth $100,000. Now after we take out $25,000 from the annuity, instead of having $75,000 left we’ll only have $73,748.65. You need to explain yourself, Mr. Wormwood.”

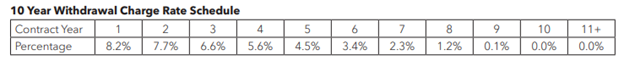

Mr. Wormwood: [Sighs loudly] “Oh boy, I guess you didn’t read the fine print. This annuity has a surrender charge if you plan to take more than 10% of the original amount you put in any one year. The length of time that this surrender charge is applicable is called the surrender schedule. The surrender schedule on this annuity is for 10 years. Here is the schedule:

You want to take money out in year 2. You put in $100,000. You can take out up to $10,000 this year without incurring a surrender penalty. However, you still need another $15,000 this year to get your full $25,000 net. To get $15,000 using the above surrender schedule, you need to withdraw $16,251.35. Therefore, you need to take out $26,251.35 to net $25,000 from your annuity.”

Mrs. Adams: “This is not what we discussed when we initially met. You knew my husband’s health was declining and that we may need this money in the future. We could have just moved all of the money that was in the brokerage account to our bank account and be better off. At least a checking account doesn’t have a surrender charge.”

Mr. Wormwood: “I’m sorry, but I thought you understood the product’s risks before you bought it. I would have read the contract before signing.”

Mrs. Adams: “Frankly your brashness is very rude. We’re going to find another advisor who has our best interest in mind and is a fiduciary who can help us clean up this mess.”

Mr. Wormwood: “Go ahead. Words of advice to you. Learn what ‘Caveat Emptor’ means.”

This is probably not the closing remark you’d want to hear from someone messing with your life savings like that. In the earlier example, Mr. Wormwood can act so aloof because he already got paid his commission up-front. As a rule of thumb, a fully up-front commission on an annuity is the number of years of the surrender schedule expressed as a percentage. In the example, it was a $100,000 annuity and a 10-year surrender schedule annuity, so there was a 10% up-front commission on the annuity sale, or $10,000. Mr. Wormwood has to share some of that commission with the broker-dealer but gets to keep most of the commission (usually 70-85%). Even if Mr. Wormwood keeps 70% of the commission, that’s still $7,000 for one sale.

Now what if the situation was different? Maybe Mr. and Mrs. Adams are instead in their 50s, in excellent health, and have $5 million in the bank. They give $7,000 every year to the American Cancer Society (ACS) and want to make sure that ACS gets that money regardless of how long Mr. and Mrs. Adams live. Now that annuity could make more sense. Another thing to note is that some annuities don’t have a surrender schedule (the client can take out as much as they want from the annuity whenever they want) and the advisor doesn’t have to earn a commission on it. The advisor instead can choose to earn an annual fee based on the percentage of the annuity’s value. Many advisors don’t since they would rather, for example, charge 10% up-front instead of 0.50% per year since the latter fee structure would take 20 years to match (assuming no growth on the annuity) what could be earned in one-year with the former fee structure of just charging 10% up-front.

I write all of this as a friendly PSA to always ask how the advisor gets paid, how much they’ll get paid, and do your research before making a big investment decision.

Cash Value Life Insurance

Another product that can either be a vital crux in someone’s financial plan or a nightmare on a client’s monthly cash flow is life insurance. This variability in outcomes has to do with either misdiagnosing or misunderstanding the client’s needs. As with annuities, you have to be on your guard when discussing life insurance with a life insurance agent. Make sure that you are working with someone with your best interest in mind at all times. Whether or not life insurance is needed can be summed up in one question. If you were to pass away unexpectedly, would your surviving loved ones who are currently financially dependent on you be able to continue living at the same standard of living that they are now? If the answer is yes, you can skip this section. You don’t need life insurance. If the answer is no, read on. You need life insurance. The questions now are how much life insurance do you need, how long do you need that protection for, and how much should you pay for that protection?

Scenario:

Mr. and Mrs. New-Parent are 40 years old and just gave birth to their daughter Sam last month. They don’t plan on having any more kids, but they want to make sure they have the funds to raise their daughter until age 18. After Sam is an adult at 18, she is on her own in their minds. Mr. New-Parent is a chemistry teacher and Mrs. New-Parent is a successful lawyer who would each be able to fund their lifestyle on their own if one of them were to pass away prematurely, so there is no need for life insurance after their daughter Sam is out of the house.

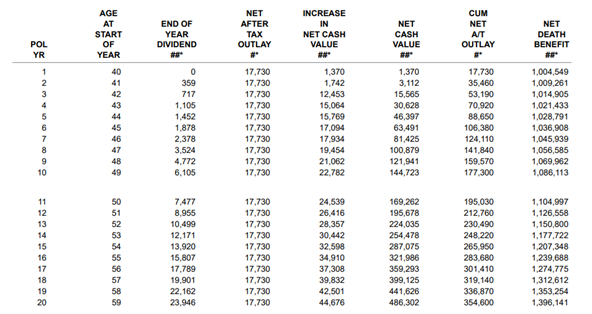

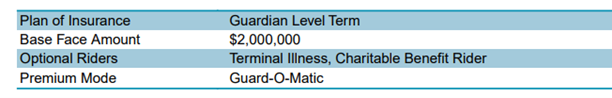

They had their financial planner do a financial plan for them and they determined that they would each need $1,000,000 of life insurance coverage to meet their goal. Mr. New-Parent decides to ask around his office for recommendations for life insurance agents. His colleague gives him a glowing recommendation for their life insurance agent, Mr. Sleaze. Mr. New-Parent meets with Mr. Sleaze and is presented with the following illustration:

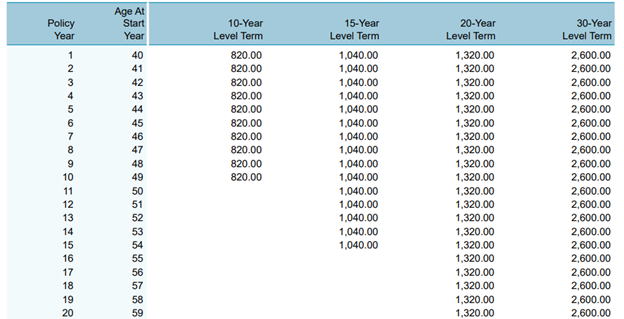

Mr. New-Parent believes that this is a good deal, thinking to himself, “Only $17,730 per year and I get at least $1,000,000 in death benefit coverage regardless of how long I live?” I need to talk to the missus.” Mrs. New-Parent hears the pitch from Mr. New-Parent and is skeptical of Mr. Sleaze’s intentions. Mrs. New-Parent went to a different agent, Mr. Agent, and was presented with the following illustration:

Mrs. New-Parent exclaimed, “Mr. Agent can get me a way better deal, $1,320 per year for $2,000,000 of coverage guaranteed. We only need $1m, but I’m just showing you I can get even more coverage for less money from Mr. Agent than you can with Mr. Sleaze. We’re going with Mr. Agent”. Mr. New-Parent thinks to himself, “Huh. With a name like Mr. Sleaze, you’d think he would get me the best deal.” Mr. New-Parent (still not believing in irony or foreshadowing) strangely wants to fight for Mr. Sleaze’s honor because Mr. Sleaze took him to lunch at Chris Ruth’s Steakhouse, and thoroughly enjoyed the meal. However, Mrs. New-Parent doesn’t buy Mr. New-Parent’s arguments. Mrs. New-Parent retorts, “We don’t need life insurance coverage for more than 20 years and Mr. Sleaze’s policy is way too expensive. Yes, the death benefit can increase but it is not guaranteed to increase.” After a brief period of argumentative back and forth, Mr. New-Parent admits defeat. “Yes, dear. You’re right. We’ll go talk to Mr. Agent and buy the life insurance policies from him.”, Mr. New-Parent agrees.

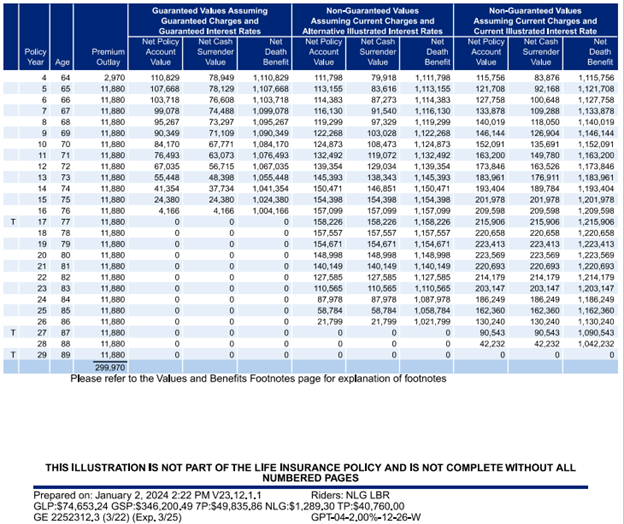

You could be thinking, if both policies met the goal of life insurance coverage over the 20 years the clients asked for, why is Mr. Sleaze’s recommendation inappropriate? It is inappropriate because they only need the coverage for 20 years. While they are both successful, $17,730 per year (or $35,460 for both of them) is a lot to handle for new parents. $1,320 per year combined (or $660/yr. each) is much more manageable than a $35,460 annual combined bill. Why would Mr. Sleaze make that recommendation? Well similarly to the annuity section, life insurance gets paid way more for doing a cash value life insurance than in a term life insurance case. Another real client case we worked with illustrates how much the agent can get paid for a $1m cash value life insurance policy. We’ll play a game of “Where’s the commission?” See if you can find which number is the number the amount the life insurance salesperson gets paid in commission:

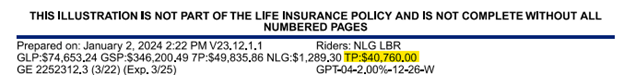

Did you find the number? Don’t worry, I won’t make you hunt for it. Here it is, highlighted:

$40,760! That’s a pretty hefty payday for Mr. Sleaze. You can buy a whole lot of T. Bone Steaks at Chris Ruth’s Steakhouse for that. Though Mr. Sleaze does have to share that commission with the agency he’s affiliated with, he’ll still end up with most of that commission. Term-life insurance commissions pale in comparison to cash-value life insurance. Instead of a $40,000 commission, that same policy as a term life insurance policy’s commission would be closer to $40. Again, it’s important to be cognizant of what you’re buying and the motives of the person selling you the product.

Private Alternatives

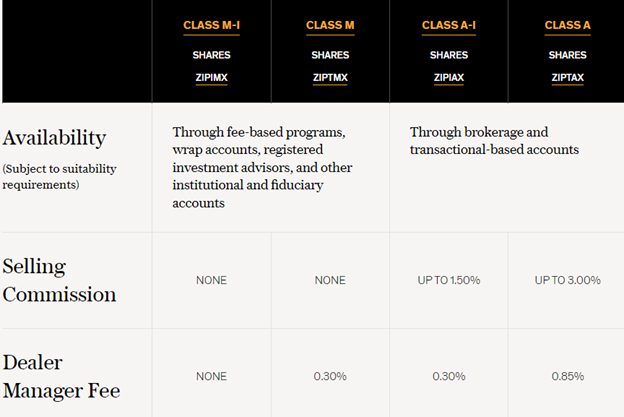

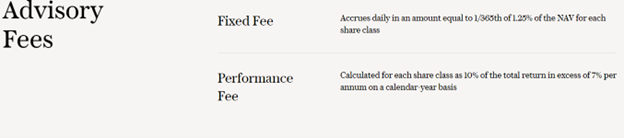

If you’ve made it this far into the article, you may have noticed a growing theme. Read the fine print and understand how the person selling you a product is getting paid. To illustrate this, we have an example of a fee structure offered by a private real estate investment. There are different ways an advisor offering the product can be paid, typically through the share class of the fund. This is highlighted below:

All of the share classes invest in the same investment, but some of these share classes can be better than others for your wallet. Compare Class M-I shares to Class A shares. Class A shares can pay the advisor a selling commission of up to 3% and would have an ongoing dealer manager fee of 0.85% per year on top of the 1.25% annual advisory fee. Before you think about an investment in Class A of this fund, keep in mind you need to pay the person selling you the fund 3% up-front and then 2.10% per year.

Compare this to the Class M-I fund, where there is no selling commission or dealer manager fee. There is still an advisory fee of 1.25% per year. You may be thinking to yourself, “What does the advisor make then?”. The advisor would add an annual fee of typically 0.50% – 0.75% for this type of investment. All in with the Class M-I share, you would pay anywhere from 1.75% – 2% per year and there is no up-front commission. Say if you were investing $100,000 into this alternative investment. Here are the fees for the Class A version of the investment:

$100,000 x 3% = $3,000 up-front commission

$100,000 x 0.85% = $850 annual dealer-manager fee

$100,000 x 1.25% = $1,250 annual advisory fee

Here are the same fees for a class M-I version of the investment:

$100,000 x 1.25% = $1,250 annual advisory fee

$100,000 x (0.50% to 0.75%) = $500 – $750 annual fee

You save $100 to $350 per year by choosing the Class M-I share class over the Class A share class and you avoid the $3,000 up-front commission. Over 10 years, that’s $4,000 – $6,500 of savings in just doing your homework and working with an advisor who isn’t compensated on selling commissions. If an investment like this is right for you, it would behoove you to pay the least amount you can for it. Your wallet will thank you.

Conclusion

In summary, do your homework. If you’re looking for a new car, you’re probably reading consumer reports. There’s a “Consumer Reports” for advisors and it’s called broker check: https://brokercheck.finra.org/.

Feel free to put in any of our names or advisors you are looking to work with in there and see if they have a disciplinary record. Also, make sure you work with someone who has your best interest in mind. Hopefully, I’ve illustrated that BFSG is a fiduciary through this article. To analogize, if the baker making the cake is giving you the cake recipe, the extra step the fiduciary takes is telling you whether or not you should even eat that cake in the first place. It could be empty calories that only sweeten the baker’s bottom line, or it could be a satisfying addition to your investment portfolio meal.

Education and understanding of your financial picture are more important to us than just following your financial plan. Now you know what questions to ask your advisor the next time you are confronted with the prospect of investing or allocating assets toward any of these products. For reference, they are:

- How much and how are you getting paid?

- Are you a fiduciary? Do you have my best interest in mind?

- How does this change to my current financial picture benefit me and is it necessary?

If you were sold something you don’t believe is appropriate for you or would like an unbiased opinion on your financial plan, please call us at 714-282-1566 or email us at financialplanning@bfsg.com.

Sources:

- https://www.wealthmanagement.com/industry/advisors-rank-almost-low-mechanics-trustworthiness

- https://jllipt.com/offering/summary

Disclosure: BFSG does not make any representations or warranties as to the accuracy, timeliness, suitability, completeness, or relevance of any information prepared by any unaffiliated third party, whether linked to BFSG’s website or blog or incorporated herein and takes no responsibility for any such content. All such information is provided solely for convenience purposes only and all users thereof should be guided accordingly. Please remember that different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that the future performance of any specific investment or investment strategy (including those undertaken or recommended by Company), will be profitable or equal any historical performance level(s). Please see important disclosure information here.